The bulb end can be hit repeatedly and not break, but the thin tail will make the entire tempered glass object disintegrate if it has the slightest graze.

This video, filmed at 130,000 frames per second and replayed in slow-motion, reveals exactly how the glass does not merely shatter but actually explodes.

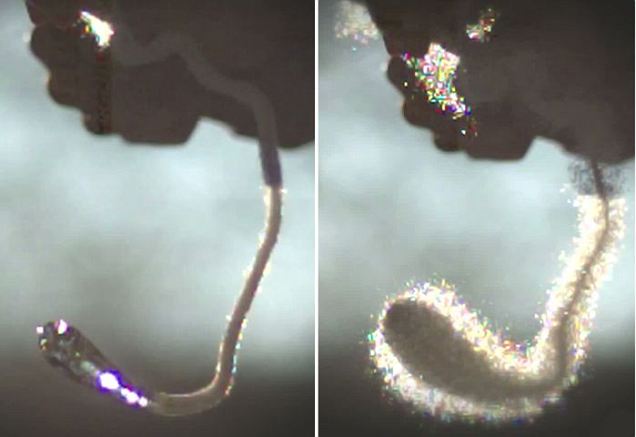

Explosion: The mystery of the Prince Rupert's Drop is revealed by filming it splinter apart at 130,000 frames per second

Hammer blow: The bulbous end of the teardrop-shaped glass is very sturdy and can withstand high impact

Tapering tail: While the front end is strong, the weak part of the teardrop shape is the thin end, which shatters the whole object quicker than the eye can see

The tadpole-shaped glass is tightly compressed inside and explodes because of the strain of different temperatures within.

By dropping a blob of molten glass into cold water, and leaving it to cool, the glass hardens at different rates creating that inner tension.

When the molten glass cools too rapidly in the water, it creates stress in the middle of the glass, because the middle of the glass is warm while the outside has cooled faster.

This means that the warmer glass in the middle pushes out against the colder outer edge.

Spectacular: Because of all the tension within the glass, when it breaks it explodes into a fine powder rather than shattering into shards like ordinary glass

Tension: All the potential energy within the glass is released from the tiniest fracture when the thin end is scratched

When the molten glass on the inside does eventually cool, it contracts and creates that inner tension.

So if the surface of the thin, tail end is scratched, the glass releases all the internal stress with such force that the entire piece shatters into fine powder, from all the potential energy locked inside.

A crack at the tail end runs all the way through the glass to its bulbous end so fast that it needs to be watched in slow motion to see it at work.

Compressed: The glass has frozen at a different temperature on the outside to that on the inside leaving it with fault lines that create stress running through the middle

Gentle pressure: From the tail to the drop end the slow motion film shows how the glass manages to be so tough and also fragile within the same piece as it explodes down the middle

Fragile: Watching in slow motion, the tension pushing out from the middle shows the glass disintegrate into crystalline powder

Stunning: The whole tear-drop glass disintegrates in a chain reaction travelling at a speed of over 1 mile per second

The Prince Rupert's Drop can even explode spontaneously because it contains so much tension.

HISTORY OF A PHYSICS PUZZLE

Prince Rupert of Bavaria (1619-1682), grandson of James I, brought the glass teardrops to Charles II as a gift.

Demonstrations of the stress of glass were introduced to England as a curious party trick.

In 1661, King Charles asked his personal scientific society, which later evolved into the Royal Society, to investigate.

No one could give Charles Il a satisfactory explanation of the extraordinary behaviour of how the trick worked.

One of the scientists investigating was Robert Hooke, who became famous for Hooke's Law.

It was not until 1994 that scientists at Cambridge University and Purdue University in Indiana solved the puzzle.

In the video, you can see how the energy moves through the exploding glass by the filming through the polariscope.

If you want to avoid these internal stresses that cause the glass to break you would 'anneal' the glass to make it less fragile.

The annealing process keeps the whole object at a uniform temperature, so that there is no internal temperature difference.

Normal glass is strengthened by slow cooling in order to reduce the brittleness.

When the drop was first introduced to England to Charles II by his nephew Prince Rupert of Bavaria, King Charles would get a subject to hold the bulb end in their hands while he broke the tip, creating an explosion in the unwitting person's hand.

However, It was not as dangerous as it sounds because the glass shatters into powder, and not shards like normal glass.

Mystery solved: Scientists had been trying to work out how the trick worked since the 1640s. It was only in 1994 that the chain reaction within the glass was finally explained